The Digger’s Diary: The story behind the book

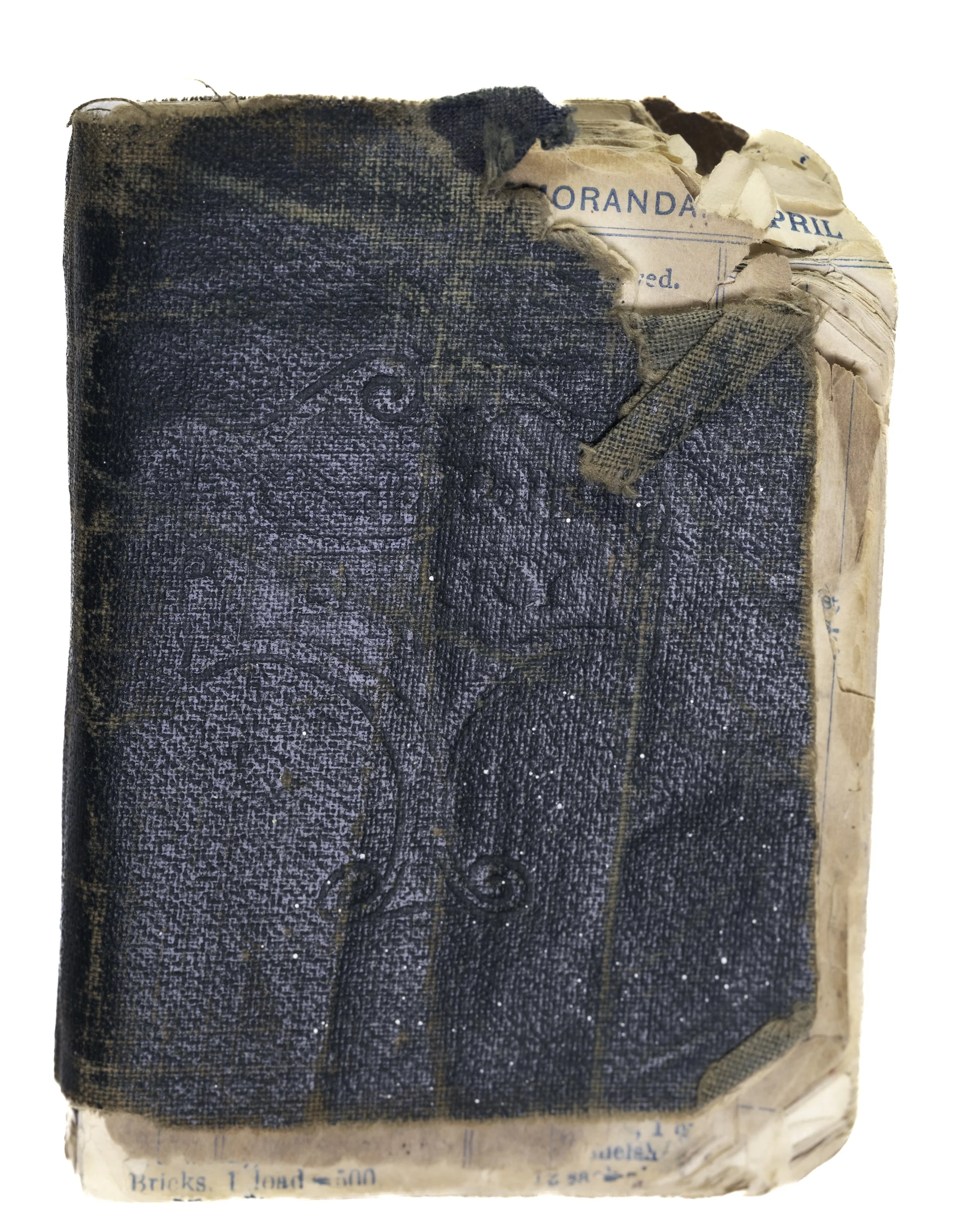

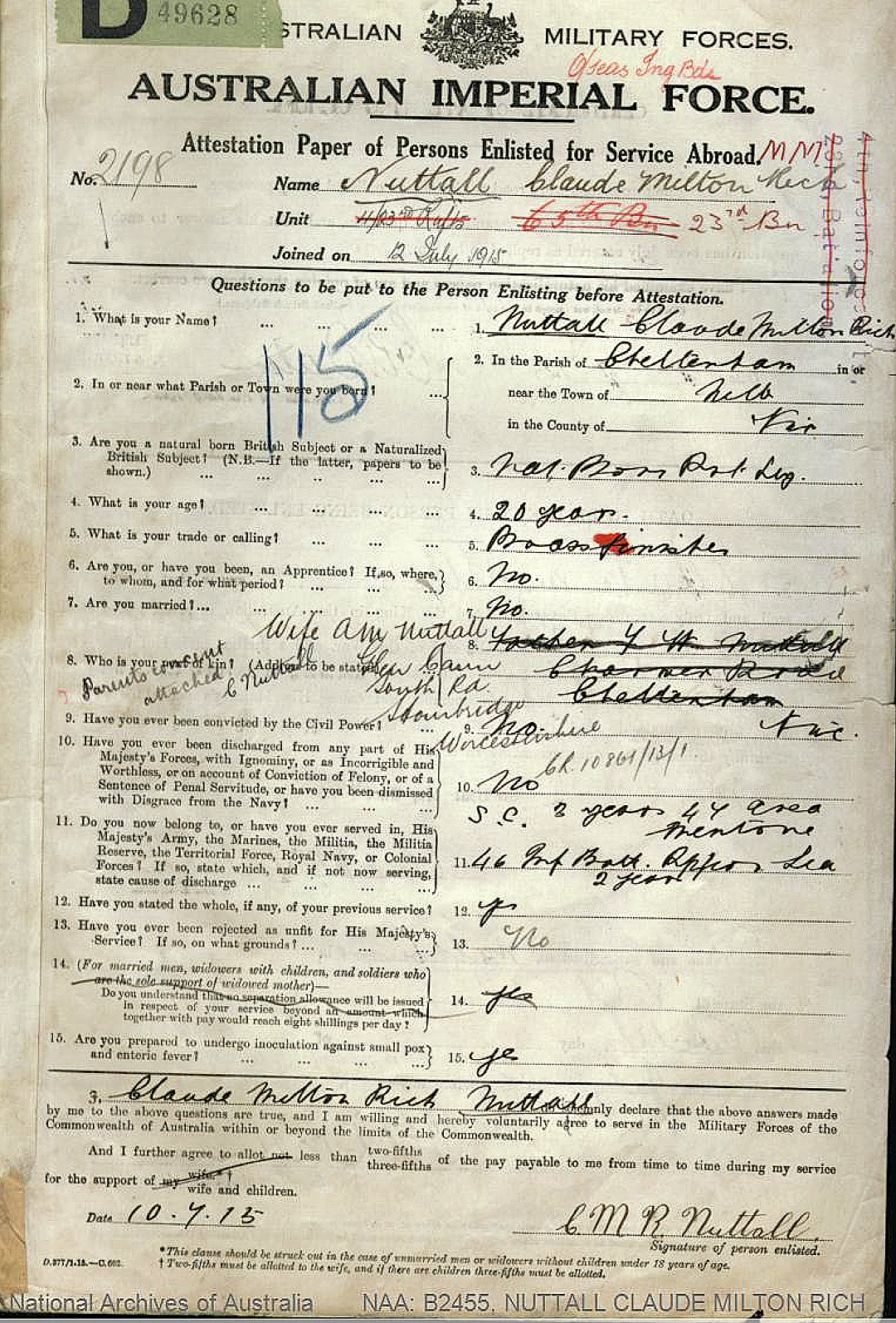

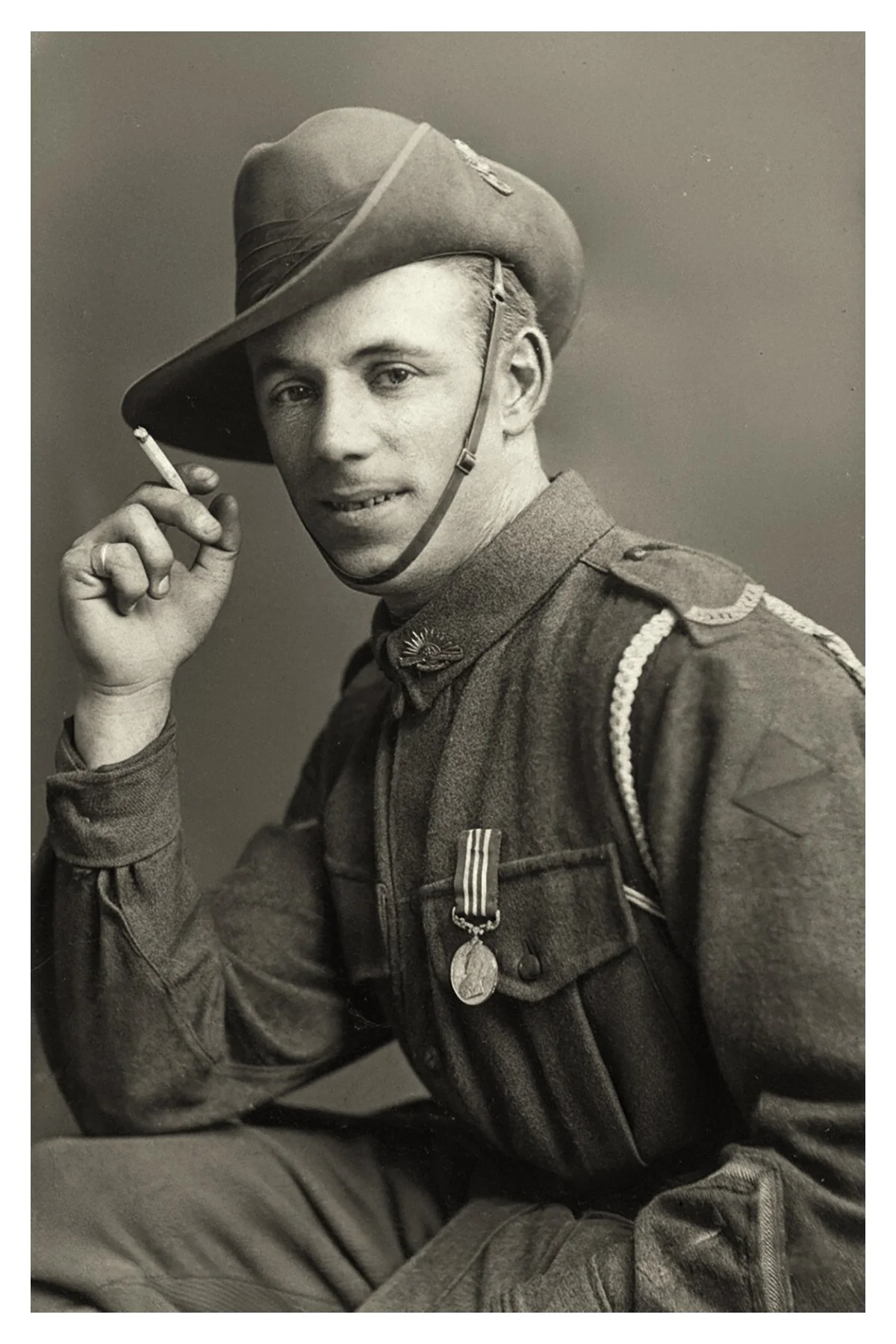

In September 1965, a small 1918 pocket diary, its soiled pages flapping in the breeze, lay discarded on a rubbish tip at Stourbridge in the English West Midlands. By chance, it was found by a 12-year-old boy called Alan Southall, while foraging with his friends. The name on the diary was Corporal Claude Nuttall, an infantryman (or ‘Digger’) of the 23rd Battalion, Australian Imperial Force.

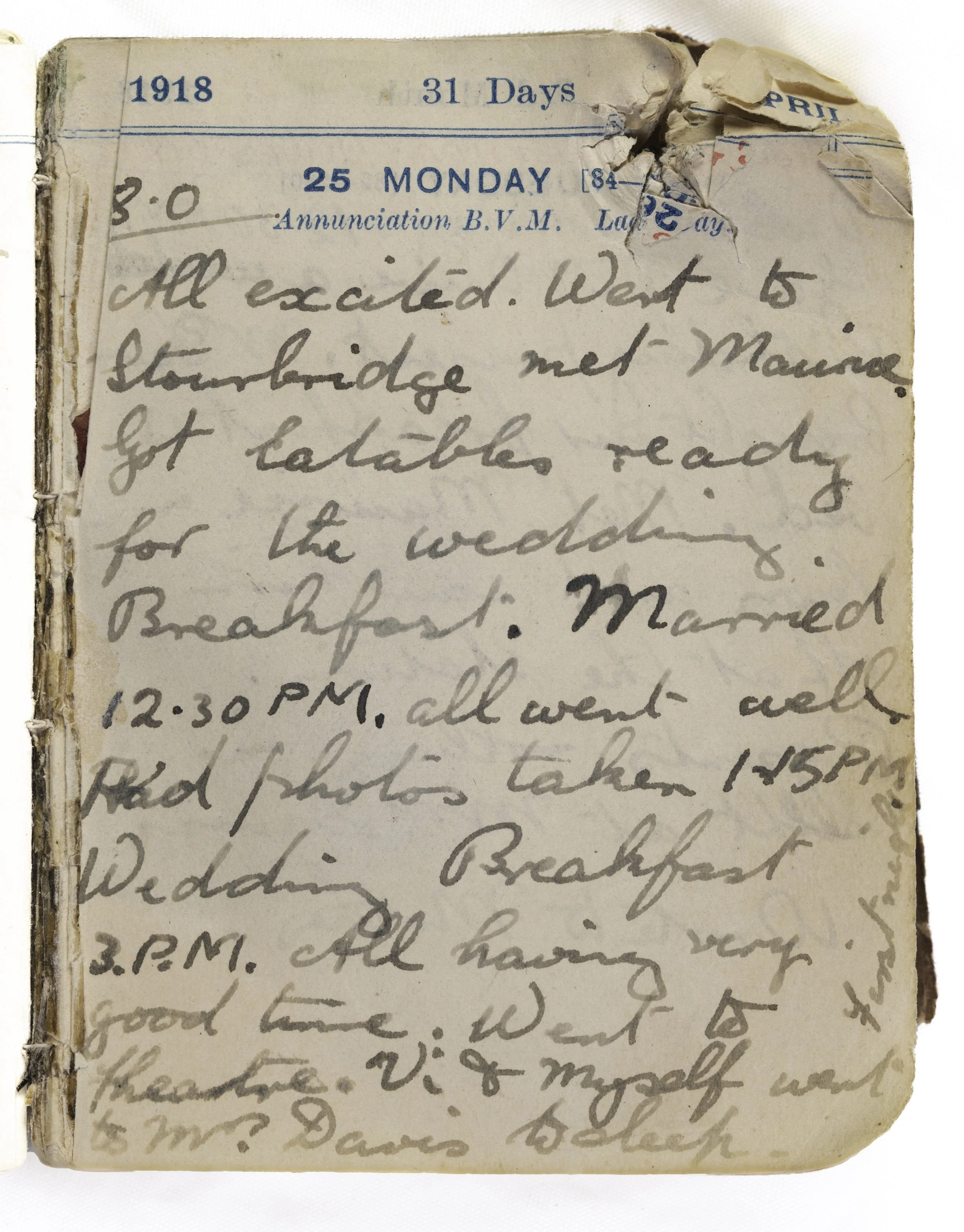

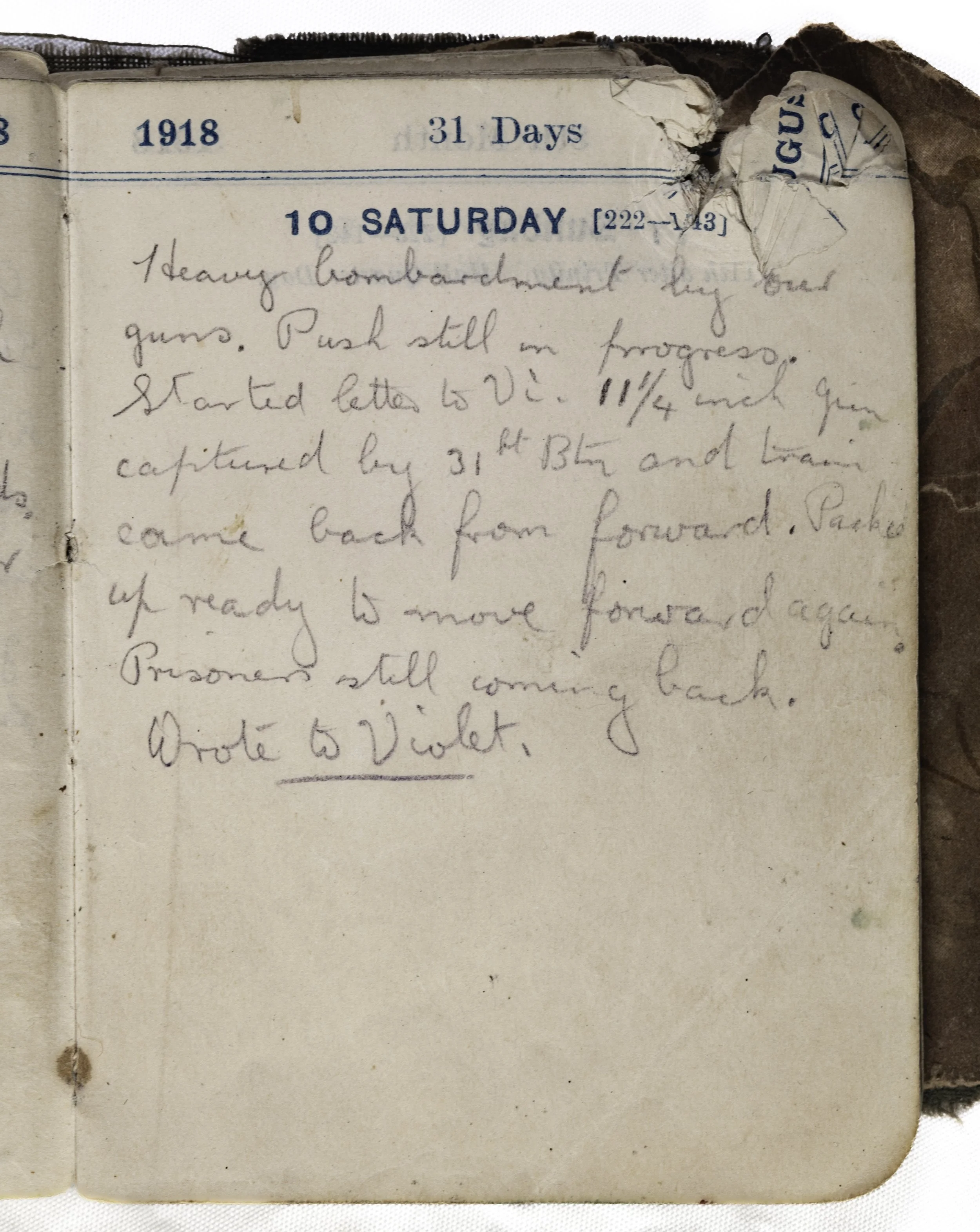

The diary’s brief entries recorded his life as a bombing instructor in Wiltshire, following a period of recovery in Stourbridge hospital from a shrapnel wound. While there, he married an English girl, Violet Palfreyman, before returning to the Western Front—where his diary entries ended abruptly. Dried bloodstains and a bullet hole in the top corner of the diary suggested an ominous fate.

In 1996, Alan Southall, now a middle-aged man, offered me the diary for an exhibition I was curating on the First World War. What began as professional curiosity would become a 22-year quest spanning three continents. My attempts to solve the mystery of Claude's fate would uncover a poignant wartime love story, a Military Medal citation for extraordinary bravery under fire…and the truth behind the bullet hole in Claude’s diary.

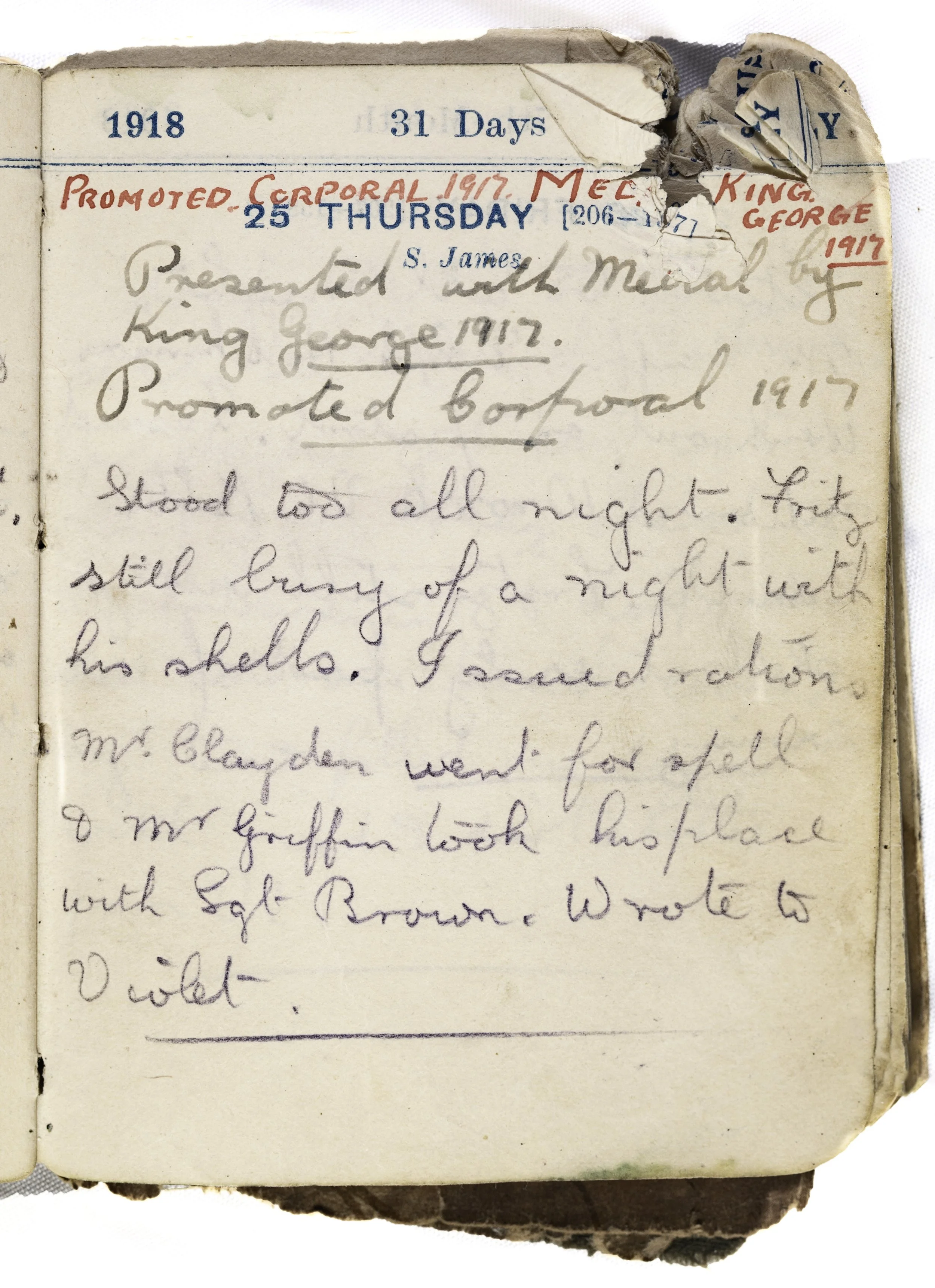

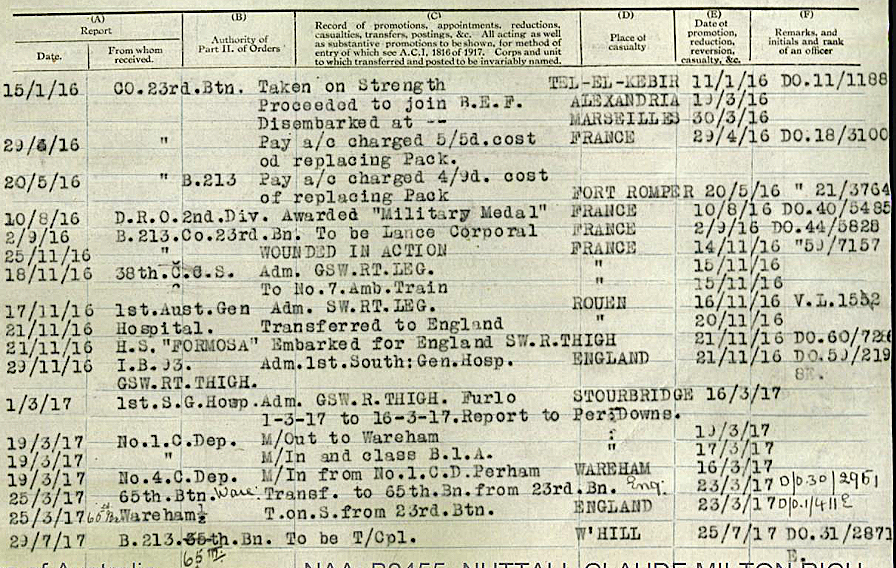

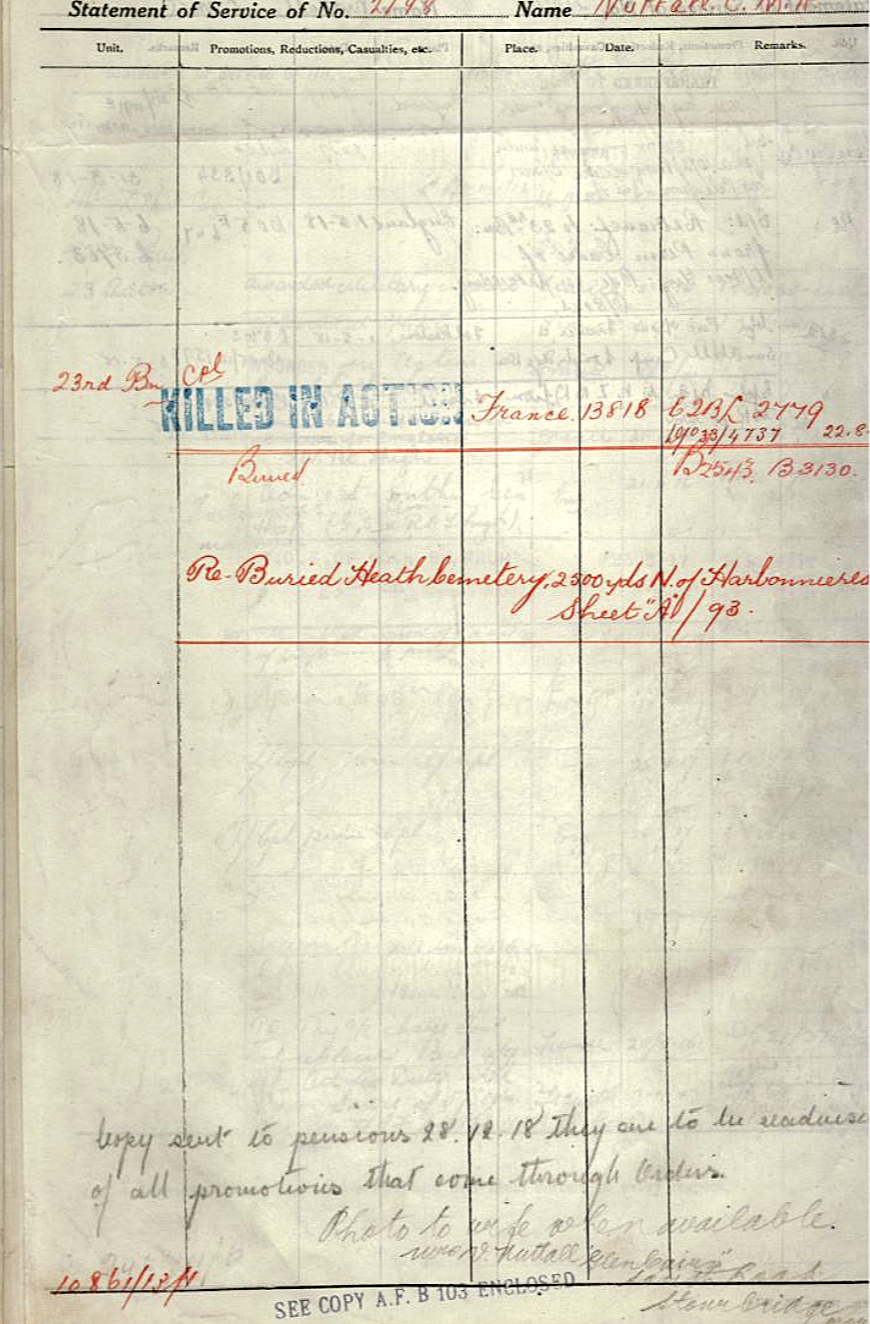

My investigations in 1996 began with a press release to solve the mystery of Claude’s fate. It made front-page news, but was unsuccessful. Then, through a contact in the Western Front Association, I received the corporal’s service records from Australia. They described how he had helped rescue injured comrades in no-man's-land on the morning of his 21st birthday, and been decorated by King George V for his bravery. They also revealed his fate in 1918: Claude was killed in action on 13th August, three days after his last diary entry.

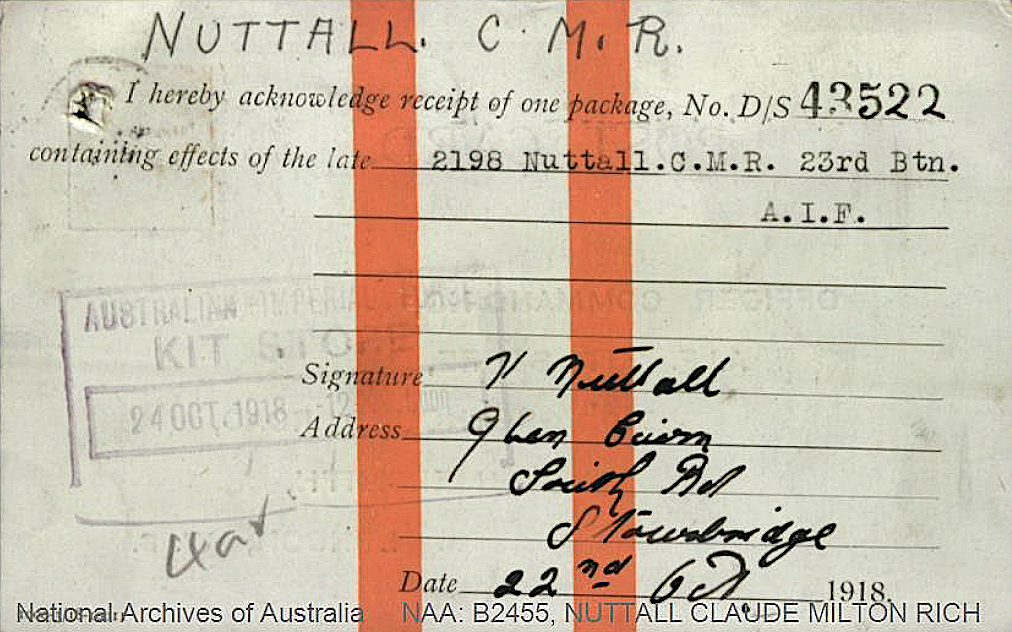

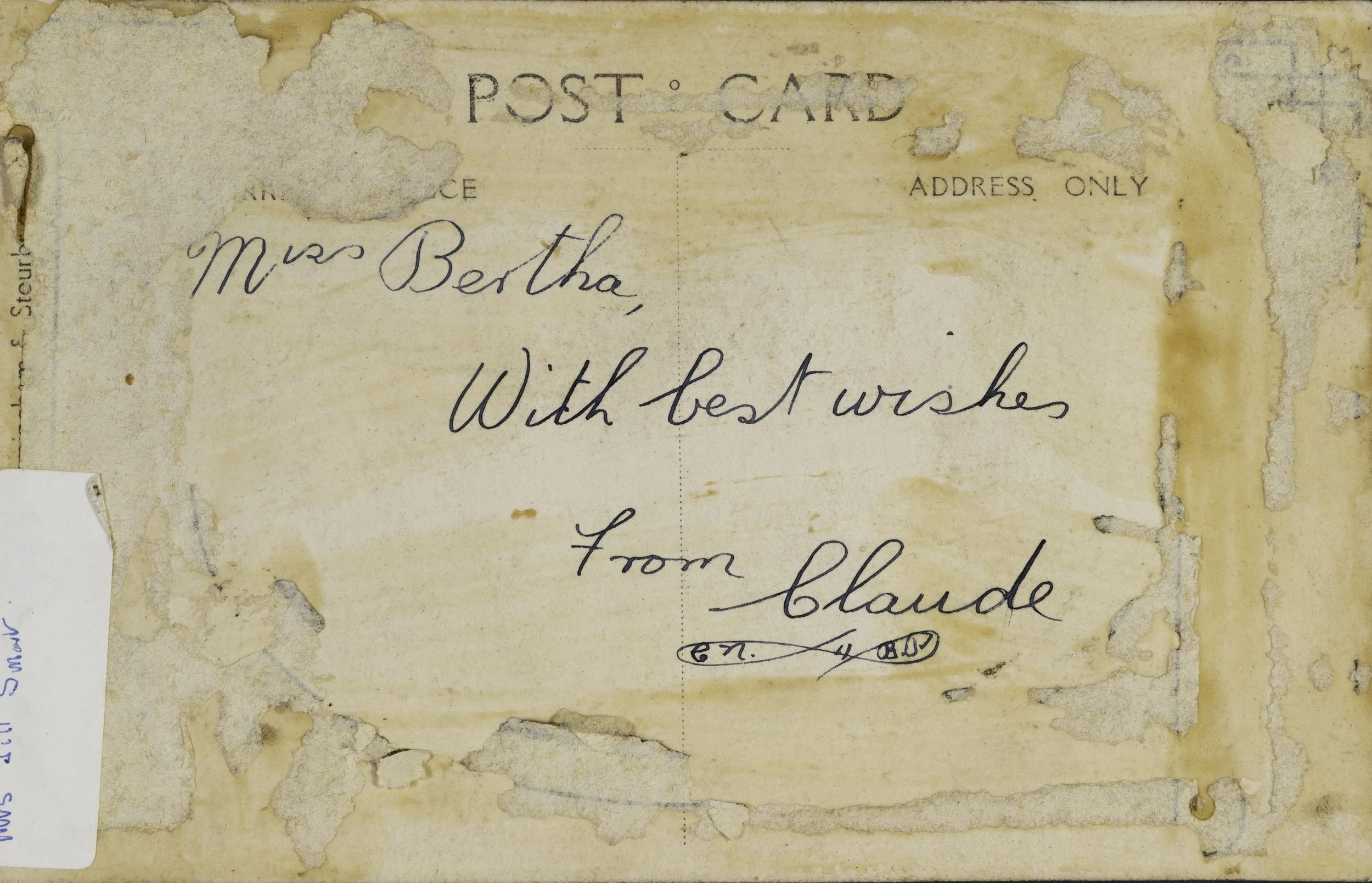

Unexpectedly, Violet's nephew, Paul Hill, and her great-niece, Jill Smart, came forward with Claude and Violet’s wedding photographs, letters, and details about Violet's life after Claude's death, including a second marriage, the birth of a son and her own early death due to complications in childbirth. Claude’s diary and effects were displayed in Dudley Museum’s Great War exhibition. You can see an original Central News item on the exhibition ‘Great War’ exhibition.

The diary exhibit became a shrine, receiving floral tributes, and touching hundreds of lives.

For years I would recount the story of Claude Nuttall’s diary to friends and acquaintances. Then, a decade later, while working in the Emirate of Sharjah, I was encouraged to write a book about the diary. My first challenge was to locate it again. Returning to England, I eventually tracked down Alan Southall, who entrusted the diary to me. Then I began my quest in earnest.

I began by trying to trace Claude’s living relatives, by sending a mailshot to every Nuttall household in his home city of Melbourne. By chance, Jessie Brent, a local history enthusiast, received the letter and, through a "Desperately Seeking" advert in the Herald Sun, tracked down Claude’s nephew Arthur Thomas and great-niece Sandra McGuiness.

This connection opened the door to details about Claude's life in Australia before the war. In 2009, I travelled to Melbourne to meet Arthur, Sandra, and Jessie, sharing the diary with them for the first time in an emotional encounter.

During the following decade, I undertook a series of pilgrimages to the battlefields of France, walking in Claude's footsteps at Bois Grenier and the Somme. I gained a visceral understanding of the horrors he endured, tracing his muddy footsteps at Pozières, where he lost 23,000 comrades, killed and wounded, over six bloody weeks in the summer of 1916. Then to Flers, where a ‘Blighty’ wound put paid to his time in the trenches for eighteen months.

My quest reached its climax on 13th August 2018, exactly a century after Claude's death, when together with Arthur Thomas and Alan Southall I visited the very spot where he was killed, and paid a tearful tribute at his graveside. It was an intensely emotional moment of closure and remembrance.

Four months later, on Armistice Day, 2018. I arranged the surprise return of the diary to Claude's family during a memorial service at his childhood church in Cheltenham, Australia, bringing its century-long journey to a poignant end.

Five years later, on Remembrance Sunday 2023, I was invited to give a eulogy to Claude during the annual commemoration at Pozières. Afterwards, civic dignitaries from Somme villages gathered at his graveside at Heath Cemetery, Harbonnières, to honour his sacrifice, lowering French flags over his headstone. The event marked the corporal’s extraordinary elevation from obscurity to veneration by the people of the nation he fought to liberate.

Why ‘The Digger's Diary’ matters

The Digger’s Diary is of universal significance: a powerful meditation on the human cost of war – a lesson urgently needed in our turbulent age.

The importance of our Tangible Heritage

The story of Claude Nuttall's diary illustrates how much we gain when we preserve and honour the vestiges of our past—and how much we lose when we discard them. Historical artefacts are irreplaceable windows into lived experience. When we dispose of them, we sever our connection to the past, losing touch with the lives that shaped our present.

The Impact of Conflict on Ordinary People

The Digger's Diary shows the human cost of war in a way a history textbook never can. It has a resonance beyond statistics and political rhetoric. The book shows the futility of war by conveying the physical and psychological damage it inflicts not only on those called to fight, but on ordinary people who have become innocent victims. In Claude Nuttall’s case, his loss left a grieving widow and a bereft family robbed of a son and brother, with no opportunity for closure.

The Sanctity of Human Life

The Digger's Diary arrives at a moment in history when the world seems embroiled in conflict, and where, more than ever, human lives seem to have little value. The story reminds us that individual lives matter, that sacrifice deserves remembrance, and that our common humanity is something to be cherished, not flouted.